I love Nanci Griffith’s voice, and I love the songs she sings. For years I listened to one of her early albums, the one with songs about race hatred and about her sister (not very flatteringly) and about going down the road with the radio on. A few nights ago I started to play another album on Spotify. My favorite song from this one has a chorus, It’s a long long way from someplace to here. I couldn’t quite make out what she was singing: There to here? Where to here? I finally listened more closely to the lyrics, about missing home, about drinking to soften the pain. Clare.

It’s a long long way from Clare to here, it’s a long long way, gets further every day.

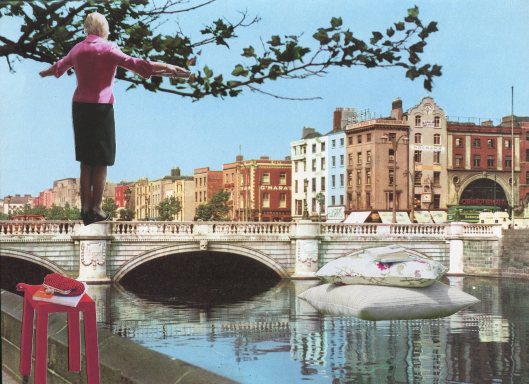

This is a song about Irish emigration.

The Irish were among the first of the immigrants to the U.S. in the nineteenth century, although for many Irish leaving their home was not an option they would have willingly chosen. They came in great waves, mostly with nothing, fleeing an island that was starving to death. Some were shipped away like so many cattle, given passage to rid the British of the dying. They landed in New York and stayed there or went the short distance to Boston. Others, mainly the ones who could afford it, spread out across the country, some to tie their fate to the goldmines and business prospects of San Francisco. Mostly they lived in ghettos and did the menial jobs, cleaning and mining and digging ditches and minding the horses. And all the time, they missed home, even though home was for these exiles a cottage or worse on land they didn’t own. They farmed it but couldn’t eat the food they cultivated—that was exported for profit by the English landlords– except for the potatoes that grew so generously in the loamy soil, until they didn’t.

The Irish were among the first of the immigrants to the U.S. in the nineteenth century, although for many Irish leaving their home was not an option they would have willingly chosen. They came in great waves, mostly with nothing, fleeing an island that was starving to death. Some were shipped away like so many cattle, given passage to rid the British of the dying. They landed in New York and stayed there or went the short distance to Boston. Others, mainly the ones who could afford it, spread out across the country, some to tie their fate to the goldmines and business prospects of San Francisco. Mostly they lived in ghettos and did the menial jobs, cleaning and mining and digging ditches and minding the horses. And all the time, they missed home, even though home was for these exiles a cottage or worse on land they didn’t own. They farmed it but couldn’t eat the food they cultivated—that was exported for profit by the English landlords– except for the potatoes that grew so generously in the loamy soil, until they didn’t.

There were signs all over America: No Irish need apply. Irish not welcome. No Irish. No Irish. They worked hard but they got reputations as drunks and brawlers. When discrimination kept them from success they resorted to dirtier politics. Ultimately they thrived, and they sent money home, to the few relatives remaining there, and then to the cause of Irish nationalism and a free state. And always, although few managed it—gets further every day–they longed to be rooted back on Irish soil.

It’s difficult not to see a connection between this longing and the over-exuberant and ultimately disastrous building during he Celtic Tiger period in Ireland. Houses built all over the island, now sitting empty. Ghost estates. Even in the new wave of prosperity, brought about after the Irish buckled to the EU’s insistence on an austerity plan and made it work, the houses are simply too numerous to fill, too isolated, not near jobs. A census completed this month identified 260,000 vacant houses a number called scandalous by the report. Nonetheless, the good news is that there are 170,000 more people in Ireland than there were in 2011. This is a small number to be sure, but in a country of 4,750,000 people a 3.7% increase is a good sign. The increase is nearly all in Dublin and its close environs; the counties of Sligo, Donegal and Mayo, all in the west, are continuing to decline, leaving populations of older adults who need public services but with few younger people to help provide and pay for it.

The houses were built because what Ireland loves, what the Irish fought for so passionately over so many centuries, is land. When the money was there the logical conclusion was to build, because who wouldn’t want to come home if the opportunity presented itself? When the Celtic Tiger collapsed, what was left were stone skeletons rising out of the earth all over the island, except in those places that needed them the most. What does a country do with 260,000 empty houses, built but mostly never occupied, but tear them down again?

![New Irish Journal VIII [diasporic edition] New Irish Journal VIII [diasporic edition]](https://newirishjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/cropped-img_0642-e1465059913933.jpg)

At the Dublin Airport for my trip back home: I bought two newspapers at WH Smith. One, the Irish Independent, is a tabloid, and although there is resistance across Ireland to division by religion no matter what the topic, this newspaper is generally seen as Catholic. The other paper I bought is the one I generally read while I’m in Ireland, The Irish Times. This paper has retained the traditional 8-column format. It is a good 2 inches wider than US papers and as such is challenging to read while sitting in economy class seats on an airplane. I bought the Times to read the news; I bought the Independent because I had had lunch with one of the arts reviewers, Sophie Gorman, while I was in Galway at the Arts Festival and wanted to see what she had to say.

At the Dublin Airport for my trip back home: I bought two newspapers at WH Smith. One, the Irish Independent, is a tabloid, and although there is resistance across Ireland to division by religion no matter what the topic, this newspaper is generally seen as Catholic. The other paper I bought is the one I generally read while I’m in Ireland, The Irish Times. This paper has retained the traditional 8-column format. It is a good 2 inches wider than US papers and as such is challenging to read while sitting in economy class seats on an airplane. I bought the Times to read the news; I bought the Independent because I had had lunch with one of the arts reviewers, Sophie Gorman, while I was in Galway at the Arts Festival and wanted to see what she had to say. Since there were no tables available I offered to have them join me. The other woman, Rachel, was an independent theatre director who had just begun a new job at the Irish Arts Council. We had all been to see three playlets by the Irish playwright Enda Walsh. The plays, each about 15 minutes in length, took place on three different small sets. In each case a small audience (2-5 people) sat in the room while a disembodied voice spoke. I had seen one of these, Room 303, last year in Galway; after seeing two more, Room 303 remained by far the best. The other two were voiced by women; I don’t think Walsh gets women, which is why most of his plays are heavily or completely male.

Since there were no tables available I offered to have them join me. The other woman, Rachel, was an independent theatre director who had just begun a new job at the Irish Arts Council. We had all been to see three playlets by the Irish playwright Enda Walsh. The plays, each about 15 minutes in length, took place on three different small sets. In each case a small audience (2-5 people) sat in the room while a disembodied voice spoke. I had seen one of these, Room 303, last year in Galway; after seeing two more, Room 303 remained by far the best. The other two were voiced by women; I don’t think Walsh gets women, which is why most of his plays are heavily or completely male.

Broadford Church matches the standard of Irish Catholic country churches. Set back from the road, these buildings rise from a cold sea of concrete and are dressed in grey stone that rain makes nearly black. Stern, cold and unadorned, these large steep-roofed edifices invite penitence; the most optimistic church-goers must feel weighted down sin by the time they arrive at the front door after crossing so much hardscape. The Church of Ireland churches, by contrast, seem almost jolly, couched as they are in small grassy enclosures with their worn round stone walls, their red wooden doors and their humble bulk, fitting for a population of Protestants that is well under 5% of the country.

Broadford Church matches the standard of Irish Catholic country churches. Set back from the road, these buildings rise from a cold sea of concrete and are dressed in grey stone that rain makes nearly black. Stern, cold and unadorned, these large steep-roofed edifices invite penitence; the most optimistic church-goers must feel weighted down sin by the time they arrive at the front door after crossing so much hardscape. The Church of Ireland churches, by contrast, seem almost jolly, couched as they are in small grassy enclosures with their worn round stone walls, their red wooden doors and their humble bulk, fitting for a population of Protestants that is well under 5% of the country. Nodlaig’s name was written in the Mass bulletin and spoken several times throughout the service by the priest. His homily was a thoughtful sermon about the Good Samaritan; Ann told me afterwards that it was more fitting for Nodlaig than the sermon on the day of her funeral. Throughout the service I pictured Nodlaig there, reciting the various creeds and beliefs (‘through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault’). As I sat and stood and kneeled and followed the service as best I could, I realized how grateful I was to be there, in the midst of her family, to think about her and especially to grieve.

Nodlaig’s name was written in the Mass bulletin and spoken several times throughout the service by the priest. His homily was a thoughtful sermon about the Good Samaritan; Ann told me afterwards that it was more fitting for Nodlaig than the sermon on the day of her funeral. Throughout the service I pictured Nodlaig there, reciting the various creeds and beliefs (‘through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault’). As I sat and stood and kneeled and followed the service as best I could, I realized how grateful I was to be there, in the midst of her family, to think about her and especially to grieve.

I had never been on such a late evening walk before, but the sky stays bright until nearly 11, and yesterday had been one of the most gorgeously sunny days I had ever seen in Ireland. By the time we drove to the end of the rocky dirt lane, more like a worn line in the earth than a road, the light was holding and the weather was balmy, with just enough breeze to keep us cool. We set out over the hill on an invisible path, going up the slight incline (what they call mountains are friendly here) and striking out through the heather and ferns.

I had never been on such a late evening walk before, but the sky stays bright until nearly 11, and yesterday had been one of the most gorgeously sunny days I had ever seen in Ireland. By the time we drove to the end of the rocky dirt lane, more like a worn line in the earth than a road, the light was holding and the weather was balmy, with just enough breeze to keep us cool. We set out over the hill on an invisible path, going up the slight incline (what they call mountains are friendly here) and striking out through the heather and ferns. I have been on very few walks in Ireland that follow established trails. Walks here are created where the walker wants them to be. Since bogland is not an issue in Tipperary, there is no need to worry about suddenly sinking up to your waist in muck. Holes and ruts in the land are another issue. The ground nearly everywhere is rough, necessitating good boots with ankle support and keen observation about where you are about to step. In these hills the general rule is to follow the sheep trails, since they invariably find the best route. For this walk Breda shared one of her hiking poles with me (the Irish don’t use the word hike; a walk is a walk whether difficult or meandering).

I have been on very few walks in Ireland that follow established trails. Walks here are created where the walker wants them to be. Since bogland is not an issue in Tipperary, there is no need to worry about suddenly sinking up to your waist in muck. Holes and ruts in the land are another issue. The ground nearly everywhere is rough, necessitating good boots with ankle support and keen observation about where you are about to step. In these hills the general rule is to follow the sheep trails, since they invariably find the best route. For this walk Breda shared one of her hiking poles with me (the Irish don’t use the word hike; a walk is a walk whether difficult or meandering). They were used in the seventeenth century for clandestine Catholic services when Catholicism was outlawed after the 1695 Penal Law. The piece used for the altar was usually taken from a church ruin and transplanted to this hidden and otherwise natural location.

They were used in the seventeenth century for clandestine Catholic services when Catholicism was outlawed after the 1695 Penal Law. The piece used for the altar was usually taken from a church ruin and transplanted to this hidden and otherwise natural location.  Services were announced by word of mouth, since they couldn’t be held at regular times. This Mass Rock, which is now commemorated with Virgin Mary statuary and a plaque, is the location for an annual pilgrimage of remembrance of the time when Catholics were refused the right to worship, priests had to register and bishops were outlawed.

Services were announced by word of mouth, since they couldn’t be held at regular times. This Mass Rock, which is now commemorated with Virgin Mary statuary and a plaque, is the location for an annual pilgrimage of remembrance of the time when Catholics were refused the right to worship, priests had to register and bishops were outlawed. After the Mass Rock the three of us moved at a more concentrated gait, aware of the gathering dark and the promise of a stop at the local pub for a well-deserved glass of Guinness. We passed an isolated cottage, owned now I was told by a 20-something Irish woman who is a sheepherder like her father in Scotland. All over Ireland these cottages exist, many in ruins but some like this one, and like the one I am staying in, brought into the twenty-first century as places of refuge, contemplation and creativity but also energy, resourcefulness and renewal.

After the Mass Rock the three of us moved at a more concentrated gait, aware of the gathering dark and the promise of a stop at the local pub for a well-deserved glass of Guinness. We passed an isolated cottage, owned now I was told by a 20-something Irish woman who is a sheepherder like her father in Scotland. All over Ireland these cottages exist, many in ruins but some like this one, and like the one I am staying in, brought into the twenty-first century as places of refuge, contemplation and creativity but also energy, resourcefulness and renewal. The next day I woke to the realization that if I didn’t go to Dublin that day I may not get there at all this trip. At 10am I hopped in the car and headed to town, not having a plan for when I got there. While on the road I decided to visit the Chester Beatty Library. I hadn’t been there in at least a couple of years, except to eat in the café. I parked at Euston Station, took the LUAS into the center of town, then walked across O’Connell Bridge and through Temple Bar, already teeming with tourists, to Dublin Castle, where the library is located.

The next day I woke to the realization that if I didn’t go to Dublin that day I may not get there at all this trip. At 10am I hopped in the car and headed to town, not having a plan for when I got there. While on the road I decided to visit the Chester Beatty Library. I hadn’t been there in at least a couple of years, except to eat in the café. I parked at Euston Station, took the LUAS into the center of town, then walked across O’Connell Bridge and through Temple Bar, already teeming with tourists, to Dublin Castle, where the library is located.

Drummin, my friend’s house, is what the Irish call a middle-sized mansion. Set back from the road on broad acreage, it is a small Georgian house, modest but still imposing, its external austerity belying the grace of the interior rooms, where he often entertains. Luncheon is at 1, beginning in the small sitting room, surrounded by books. Books are his passion; the books he orders by mail come in a steady stream. They are piled up on the floor and in front of the glass-front mahogany bookcases. One small side table always has several stacks of books perched so precariously that it looks like the table will tip over, like an outsized game of Jenga.

Drummin, my friend’s house, is what the Irish call a middle-sized mansion. Set back from the road on broad acreage, it is a small Georgian house, modest but still imposing, its external austerity belying the grace of the interior rooms, where he often entertains. Luncheon is at 1, beginning in the small sitting room, surrounded by books. Books are his passion; the books he orders by mail come in a steady stream. They are piled up on the floor and in front of the glass-front mahogany bookcases. One small side table always has several stacks of books perched so precariously that it looks like the table will tip over, like an outsized game of Jenga.